No, not that Great Wall.

The focus here is on China’s Great Wall Motor, and some of its more recent and noteworthy efforts in the EV market. More specifically, we’ll take a look at Great Wall’s new Ora brand, its joint venture with BMW, its investment in Yogomo Motors, and how all of this relates to China’s New Energy Vehicle/NEV market. For any reader that is not familiar with the NEV terminology, NEV refers mostly to EVs and hybrids, but also includes fuel-cell vehicles.

This blog also takes a look at the choices that automotive OEMs/Original Equipment Manufacturers have when responding to the Chinese government’s policies and regulations related to fuel economy standards and the NEV credit system. NEV credits are sometimes called “carbon-credits”, because they’re part of the Chinese government’s broader efforts to cut air pollution and related carbon dioxide emissions into the atmosphere.

Great Wall’s Launching of the new Ora brand

Last year Great Wall launched its new Ora brand, which stands for Open, Reliable, and Alternative. Presently, the brand has two products in the market, the Ora iQ, a compact Crossover (left side), and the Ora R1, a four-door sub-compact (right side).

The Ora iQ was launched last September, while the Ora R1 launched a few months later in late December.

A third model, the Ora R2 is expected during the third quarter of this year. A concept version appeared at the Beijing Auto Show in 2018, as seen below:

According to an Automotive News Europe article here, Great Wall plans to have a total of four Ora models on the market by 2020.

According to an Automotive News Europe article here, Great Wall plans to have a total of four Ora models on the market by 2020.

At least for now, Ora’s brand identity is oriented towards small BEVs, aka “battery electric vehicles”. BEVs are also sometimes called “pure” EVs, because they’re powered by batteries only, in contrast to PHEVs (Plug-In Hybrid Vehicles) which are powered both by fossil fuels and batteries. Small BEVs like the Ora R1 or the Ora R2 are relatively inexpensive to produce. EVs of all sizes (small-medium-large) are valuable to manufacturers because they generate NEV credits, which can be used to offset CAFC/Corporate Average Fuel Consumption credit deficits. Deficits occur when a manufacturer falls short of its fleet average target, as set by the regulator. In the case of China, the regulator is the central government’s powerful Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT). CAFC credit deficits can be expensive, because they’re synonymous with “non-compliance,” and non-compliance with the policy and regulations can result in expensive fines or other costly penalties.

Government subsidies play a major role in keeping the retail price of NEVs low. Small EVs, such as those offered through the Ora brand can have “after subsidy prices” that are below USD 10,000. Although “alternative,” is the third reference letter in the brand name (Ora), a case can be made that “affordable,” would have been equally or perhaps even more appropriate. For example, the Ora R1’s “after government subsidies” cost to the consumer, ranges between 59,800 RMB and 77,800 RMB (USD 8,917 to USD 11,601) depending on options. The affordability aspect of the brand is undoubtedly attractive to younger budget conscious consumers.

The new brand Ora, with its implicit focus on “small,” or “urban” – – must feel a bit different for Great Wall and its corporate culture. In contrast, the company’s most successful brand Haval, projects a more rugged, off-road SUV type image.

The company’s Wey brand, launched in 2017, projects “upscale”, or elevated – – and above the fray.

The company’s Wey brand, launched in 2017, projects “upscale”, or elevated – – and above the fray.

So What’s the Alternative in Ora?

I’ve reflected a bit on Ora’s “alternative” brand emphasis, and although the subliminal or intended message is not clear to me – – it strikes me that simply choosing to buy a small BEV – – is likely part of the brand’s “alternative choice” or “alternative lifestyle” messaging. Choosing to be green, or at least green-er – – is also likely part of the pitch.

Great Wall’s choice to launch the Ora brand indicates that the company sees an opportunity to establish a larger presence in China’s growing NEV market. The Ora brand appears to be targeting young car buyers that are mostly urban, budget conscious, and green – – or even a whole rainbow of colors. 😉

One of the fun aspects of Ora’s voice recognition system – – is that the system gets activated – – when the driver calls it by name – – “Ora!” – – (kind of like a wake up call – – or a like a cute puppy that comes running, as soon as it hears its name).

One of the fun aspects of Ora’s voice recognition system – – is that the system gets activated – – when the driver calls it by name – – “Ora!” – – (kind of like a wake up call – – or a like a cute puppy that comes running, as soon as it hears its name).

Great Wall, with its Ora brand, is making a more concerted effort to establish itself in China’s NEV market. Much of the sales volume in this market exists with smaller cars, and by all indications – – that looks like the market that Ora is focused on.

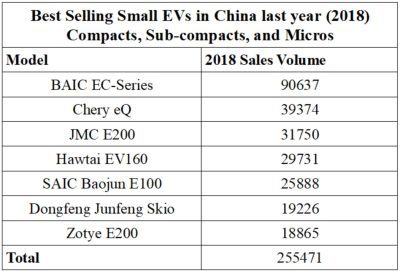

Of the Top Twenty Best-Selling NEVs in China last year (2018), seven were compacts, sub-compacts, or micros. The table below shows these seven, with their respective sales volume data. It also sheds light on at least some of the models, that Great Wall and Ora are competing against.

The seven best selling small EVs had a cumulative sales volume of more than a quarter million vehicles.

As a group (i.e. Compacts+Subcompacts+Micros) small EVs represented just over one third (37%) of the total sales volume for China’s Top Twenty Best Selling NEVs last year. So in other words; its a sizable market. This at least partially explains why Great Wall and its Ora brand are entering this market segment. Government policies and regulations related to China’s more rigorous fuel economy standards and the promotion of NEVs, also are likely having an influence. Subsequent sections of this blog explore these aspects in greater detail.

Great Wall’s earliest efforts in the NEV market; prior to the launching of Ora

Great Wall’s earliest attempts at entering into the NEV market have been – – “less than stellar.” In 2016, Great Wall launched an EV variant of its C30 sedan.

Great Wall’s earliest attempts at entering into the NEV market have been – – “less than stellar.” In 2016, Great Wall launched an EV variant of its C30 sedan.

More recently, in April of 2018, the model received an upgrade, with a higher battery capacity.

One reviewer, when reviewing the earlier version of the C30 EV – – – – made a number of interesting observations. For readers that want to see the full 2016 review, you’ll find it here. I’ve pasted some of the key points, verbatim, below:

-

The Great Wall C30 EV has been launched on the Chinese car market, …

-

The C30 EV is an electric car based on the C30 sedan, a car that is possibly more rare than a Ferrari. … Very few dealers are selling it, … so the C30 is a true rarity.

-

One might wonder why Great Wall didn’t spend the money on electrifying one of their best selling Haval SUVs, which would make much more sense than this electrifying this ancient pre-facelift version of a slow selling sedan that you cannot even buy if you really wanted to because most Great Wall dealers don’t even sell it. What is the point of it all..?

-

The point might be that Great Wall isn’t actually planning to sell any, a common trick among Chinese automakers. They just want to have some EVs on their books to bring the average fuel consumption of their lineup down, as demanded by the Chinese government.

Although, there might be other sides to this story that I’m missing (if so, I’d like to hear it), based on historical sales volume data, and the review above, it seems the C30 EV never really established much of a presence in the market.

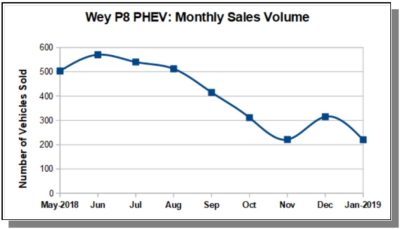

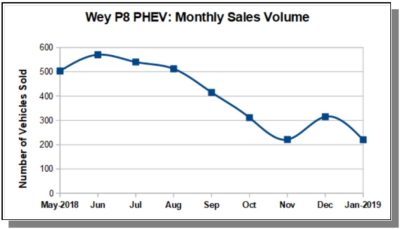

During the second quarter of 2018, Great Wall launched its second NEV, the Wey “P8” – – a PHEV SUV.

Sales volume for the P8 has been low, and trending downwards. During nearly every month since June of last year, sales have been diminishing. December, which is normally an “up-month” for the whole industry, was the exception to the trend.

Sales volume for the P8 has been low, and trending downwards. During nearly every month since June of last year, sales have been diminishing. December, which is normally an “up-month” for the whole industry, was the exception to the trend.

So considering Great Wall’s track record, both with the C30 EV, and the P8 PHEV; one might be forgiven for being skeptical about the company’s potential in the NEV sector. But taking such a view would be based on a fairly limited look at just two of its earliest models.

So considering Great Wall’s track record, both with the C30 EV, and the P8 PHEV; one might be forgiven for being skeptical about the company’s potential in the NEV sector. But taking such a view would be based on a fairly limited look at just two of its earliest models.

Great Wall revisits EVs with Ora – – Small is Beautiful

On the other hand, with the launching of the Ora brand, and with a growing market for small EVs in China, Great Wall has reasons to be optimistic. The brand appears to be off to a pretty good start. Since the Ora iQ compact Crossover was launched last September, sales volume is trending upwards. Not only that, but as seen in the graph below, nearly twice as many iQ’s were sold in January 2019 (the most recent month for which data is available), compared to the previous month.

As noted earlier, Ora’s sub-compact, the R1, was launched in late December. With just one month of data available (Jan. 2019), its too early to talk about trends. Nevertheless, the R1 seems to be off to a pretty good start with 1,749 units sold during its first month in the market. That’s more than twice the number of Ora iQ’s that were sold during its first month. It’s also not so far from the 2,036 level that the iQ reached after four months.

In addition to market demand, What else is contributing to Great Wall’s Interest in Small EVs?

In short, the answer is – – China’s recent government policies and regulations that govern fuel economy standards and the promotion of New Energy Vehicles.

More specifically, in September of 2017, China’s Ministry of Industry Information and Technology (MIIT), the government entity responsible for fuel economy standards and the promotion of New Energy Vehicles, issued a new policy:

The parallel management method for average fuel consumption of passenger car enterprises and new energy vehicle points.

The original document, that explains the policy, in Chinese, can be found here.

Luckily for non-Chinese speakers, a much shorter easier to understand explanation of key aspects of the policy exists in English here. Produced by the US government’s Library of Congress, and its Global Legal Monitor, some of the key text is highlighted below:

-

Auto companies producing or importing over 30,000 non-NEV passenger cars per year will be required to earn NEV credits equal to a set percentage of their non-NEV sales in China, starting from 2019. The NEV credit percentage targets are 10% for 2019 and 12% in 2020.

-

The percentage targets are for NEV credits, not NEV sales. Each NEV may generate multiple credits, as follows:

-

Each plug-in hybrid may generate two credits.

-

Credits each pure electric car may generate depend on the electric range.

-

Credits each fuel-cell car may generate depend on the rated power of fuel cell systems. (Id. annex II.)

-

-

For example, if a company produces 100,000 non-NEVs in China in the year 2019, with a 10% NEV goal, it needs 10,000 NEV credits. The goal may be achieved by producing 5,000 plug-in hybrids (two credits per vehicle), amounting to 5% of the company’s non-NEV sales.

-

A company generates surplus NEV credits if its actual NEV credits are greater than the NEV target and a NEV credit deficit if its actual NEV credits fall short of the target. Similarly, it generates surplus CAFC credits if its actual CAFC is lower than its CAFC target under the existing fuel consumption regulation, and a CAFC credit deficit if its actual CAFC exceeds its CAFC target.

The same source notes that China’s fuel economy standard for 2020 is 5.0L/100 km, which represents an OEM’s expected fleet wide average target. The previous standard, pegged to the end year 2015, was less efficient, at 6.9L/100 km. By comparison, the new more rigorous 2020 standard represents an impressive 28% increase in fuel efficiency.

Great Wall produces and sells mostly SUVs. Sales volume for January 2019 is graphed below, illustrating the point:

If you visit Great Wall’s China Haval website, you’ll see a product line that looks like this:

If you look at the Wey brand’s product line – – you’ll see this:

You get the picture, you’ll see a lot of SUVs. 😉

Market demand for SUVs in China, is often described as insatiable. Relative to sedans and smaller vehicle types, growth rates for the SUV market, has been, and remains strong. It’s therefore easy to understand why Great Wall’s business strategy and product line is so vested in SUVs.

But SUVs tend to be heavy, and as such, they tend to have lower fuel efficiency. The same is true for Great Wall’s Wingle brand Pickups, they’re also heavy, and their fuel economy ratings are even lower.

Because SUVs dominate Great Wall’s product line, this makes it more challenging for the company to meet and comply with the Chinese government’s more demanding fuel economy standards. If we look at the Wey product line up above, only the P8 PHEV, with its fuel economy rating of 2.3 L/100 km., comes in below the 6.9L/100 km. standard referenced above. The other three models, meaning the W5, the W6, and the W7 – – all have fuel economy ratings that are above 7 L/100 km. Although the P8 helps Great Wall with its fleet wide average, the problem is that market demand for the P8 has been tepid at best. So Great Wall can produce a lot of P8’s to bring its fleet wide average down, however if they’re not selling well – – and they’re not – – that’s a pretty expensive strategy.

A failure to comply with with the government’s more rigorous CAFC standards – – or a deficit in terms of the parallel system of earning NEV credits – – would be expensive for any and all OEMs, including Great Wall. In other words, the policy has teeth, which could negatively bite into corporate profits in a major way. The penalty for non-compliance is described in a January 2018 Policy Update here, by the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT):

Failure to meet CAFC or NEV credit targets after adopting all possible compliance pathways will lead to MIIT denial of type approval for new models that cannot meet their specific fuel consumption standards until those deficits are fully offset.

So in other words, China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) has the power to approve or deny the launching of new models into the market. A company in non-compliance status could find that it’s unable to launch and sell new models – – until it comes back into compliance. That seems like a very strong incentive to me, because, from a long term perspective, companies must get their new models to market, in order to compete and survive.

Compared to its peers, Great Wall’s adjustment to the new policies and regulations is likely to be more challenging. This was highlighted in a Bloomberg News article titled China is About to Shake Up the World of Electric Cars, which included a look at various automotive OEMs in China, and their EV “readiness.” Below, I’ve added bold to the Bloomberg text that pertains to Great Wall:

-

Companies that have a head start on producing NEVs have the highest credit scores. Those include BYD Co., BAIC BluePark New Energy Technology Co. and Geely Automobile Holdings Ltd., according to the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology. The highest negative fuel consumption credits were Ford Motor Co.’s China venture with Chongqing Changan Automobile Co., leading SUV maker Great Wall Motor Co. and Dongfeng Motor Corp.

The key words above are “negative fuel consumption credits.” Remember, Great Wall and all automotive OEMs in China have a CAFC (Corporate Average Fuel Consumption) target, set by the government, based on the fuel economy ratings of an OEM’s corporate fleet. Because Great Wall produces mostly SUVs, with relatively lower fuel economy ratings, this makes it more challenging to meet its CAFC target. As a result, Great Wall has high negative fuel consumption credits.

Negative fuel consumption credits can be addressed, or remedied, in multiple ways. Options are outlined in China: New System Relating Corporate Average Fuel Consumption to New Energy Vehicle Sales Takes Effect, and key text from that source appears below:

To offset a NEV credit deficit, a company may purchase NEV credits from other companies. To offset a CAFC credit deficit, more options are provided, including:

- using banked CAFC credits,

- transferring CAFC credits from affiliated companies,

- using self-generated NEV credits, and

- purchasing NEV credits from other companies.

Considering Great Wall’s product line, with its SUV emphasis, it seems unlikely that Great Wall has banked CAFC credits to use. In two subsequent sections below, I take a look at two of the three remaining options or remedies. Evidence suggests that Great Wall is using at least two of these options to pro-actively comply with the new government policies and regulations, that are reshaping the automotive industry and market in China.

Using self-generated NEV credits; Great Wall will get a boost; from its new brand Ora

Great Wall’s launching of the Ora brand, seems like a pretty clear response to the policy.

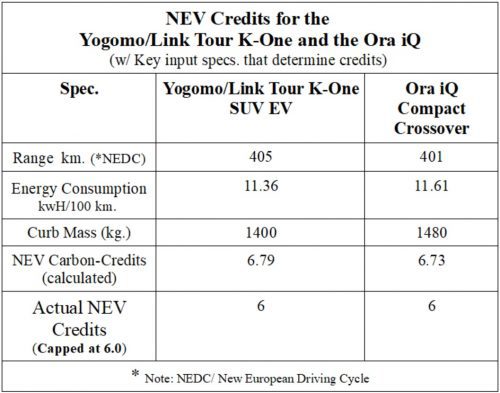

Each new Ora vehicle that rolls off the assembly line, and subsequently gets registered with the regulator (MIIT), generates NEV credits. The number of credits depends on the models specs. Range is particularly important for determining a specific NEV credit score. For pure EVs (aka BEVs), other variables such as energy consumption (kWh/100 km.) and curb mass (kg.) are also used. For a detailed explanation of how NEV credit scores are calculated, both for BEVs as well as for PHEVs, readers should consult China’s New Energy Vehicle Policy Mandate (Final Rule) by the International Council on Clean Transportation/ICCT.

Ora’s emphasis on smaller cars makes a lot of sense, because they’re relatively inexpensive to produce. There are other important benefits as well, for example, for every Ora R1 that Great Wall produces, the company earns 5.42 NEV credits. This is close to the “capped” or maximum 6.0 credits that an OEM can earn for the production of any BEV model. Ora’s compact Crossover, the iQ, on the basis of its specs alone, would earn 6.7 credits, however, because of the cap, it maxes-out at six credits. The policy and regulations apply a distinct and different cap for PHEVs. The maximum NEV credits that any PHEV can earn is two; which is the number that Great Wall earns by producing one of its Wey P8 SUV plug-in hybrids. Decisions about production quantities are primarily determined by market demand, however they’re also influenced by policies, regulations, and related factors. Whether an OEM currently has a positive or negative fuel consumption score, could be one such factor.

By extension, when OEMs with negative fuel consumption scores (eg. Great Wall, Dongfeng, or the Ford-Changan JV) decide that they’re going to use “self generated NEV credits” to improve their negative fuel consumption scores, they’re looking for an optimal or most cost-effective means for doing that. This undoubtedly includes some type of cost-benefit analysis that takes into account key variables such as the cost of production per vehicle, market demand, profit margins, and the number of NEV credits associated with each model.

While writing this blog, I came across an interesting paper about the “Impacts of China’s Subsidy Policy and New Energy Vehicle Credit Regulation …” The authors and researchers are from Tsinghua University in Beijing, one of China’s leading universities in the fields of automotive and energy research. The paper includes a detailed analysis that shed’s light on two key, and related questions:

Under the current policies and regulations, what vehicle size, benefits most from the subsidies?

Under the current policies and regulations, what vehicle size, has the highest cost- effectiveness, for earning NEV credits?

For automotive companies competing in China, and for their senior managers, these questions are important. This is particularly true for companies with negative fuel consumption scores.

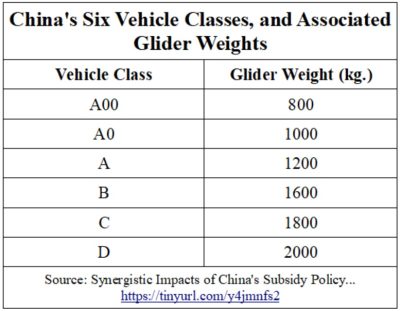

The Tsinghua University paper includes key findings and some great graphs that directly address the questions above. However, before highlighting these findings, its useful to briefly review the topic of “vehicle classes” in China, and their relationship to vehicle weight, and more specifically, to a concept called “glider weight.”

Similar to the European classification system, China has six vehicle classes (A00, A0, A, B, C, D). Glider weight, is the weight of a vehicle without a powertrain. For the sake of simplicity, glider weight can be thought of as the ease with which a vehicle coasts – – when power is not being transmitted from the engine to the vehicle’s axles. In the case of an EV, the concept is the same, but just substitute “battery and electric motor” for “engine/ICE”.

China’s system for classifying vehicles uses glider weight, along with other factors. Smaller lighter cars tend to have lower glider weight values, while the opposite is true for larger and heavier cars. The table below shows China’s six vehicle classes and their associated glider weights:

So with the benefit of now knowing a little bit more about China’s vehicle classes, we can now posit the following key question:

If you’re manufacturing cars in China, and you want to get the most from the subsidies and the NEV credit system, what types of cars (vehicle class) should you produce?

Regarding the contribution of subsidies, towards offsetting manufacturing costs, the researchers found that:

-

-

Small vehicles will consistently obtain a higher contribution rate than that of large vehicles.

-

Except for BEVs in the A00 class, the smaller the vehicle is, the higher the contribution rate becomes.

-

Overall, small vehicles and vehicles with a high driving range are encouraged by the subsidy policy. Under the subsidy, the smaller the vehicle type is, the greater the relative manufacturing costs offset by the subsidies will be.

-

The ideal circumstance is that the contribution rate decreases over time and BEVs achieve competence compared with internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles without the subsidy of the government.

-

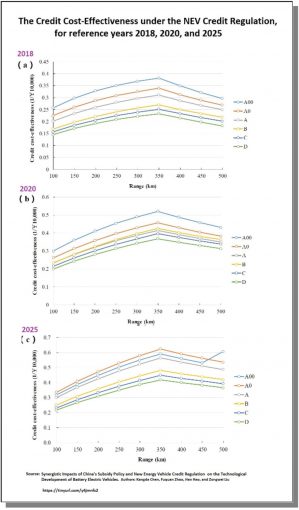

The research design carefully considered the fact that subsidies are changing and diminishing over time. For this reason, when analyzing NEV credits and cost-effectiveness, three distinct time periods (years) were used; 2018, 2020, and 2025. Within this context, it’s important to remember that subsidies will end after 2020.

The credit cost-effectiveness (for BEVs), under the NEV credit regulation, is shown in the three graphs below for each of the three reference years:

What’s noteworthy about these findings and graphs is that fairly consistently across reference years the smallest cars are the most credit cost-effective. An exception is seen in the third graph, which represents the year 2025, when small (but not the smallest) A0 class cars become more credit-cost effective.

So considering that small cars are almost always more credit cost-effective, Great Wall’s launching of the Ora brand, with its emphasis on small (i.e. compacts, and sub-compacts), makes a lot of sense.

So too, does Great Wall’s recently formed joint venture with BMW, to produce Mini brand EVs, which is described in greater detail below.

Great Wall’s Joint Venture w/ BMW, to produce Mini EVs.

Back in October of 2017, reports began to circulate about the possibility of a joint venture between BMW and Great Wall, for the purpose of producing BMW’s iconic Mini brand.

Great Wall’s investors reacted enthusiastically to these reports, and on Oct. 11th 2017, Great Wall’s stock price on the Hong Kong Exchange jumped 14 percent in a single day.

About four months later, while negotiations were still underway, a Reuters article here, highlighted some of the benefits that Great Wall was hoping to realize via the joint venture:

- Great Wall said in a separate statement a joint venture with BMW would greatly improve its technology level and brand premium, better meet the needs of consumers and further tap into the new energy vehicle market at home and abroad.

- Automakers and suppliers are scrambling to meet tough new Chinese quotas for less polluting cars, which call for electric and rechargeable hybrid vehicles to account for a fifth of total sales by 2025.

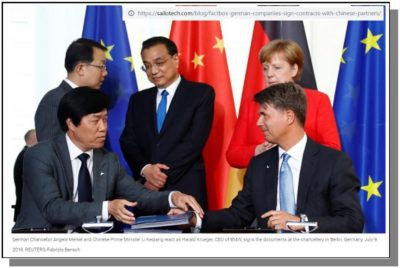

In July of 2018, the two companies finalized negotiations, and announced the creation of their new joint venture, to produce electric Minis in China.

As noted in an article here, the new venture, which goes by the name Spotlight Automotive Ltd., was celebrated by both Germany and China at the highest political levels. The signing ceremony took place in Berlin, and was attended by Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel, and China’s Premier Li Keqiang.

As noted in an article here, the new venture, which goes by the name Spotlight Automotive Ltd., was celebrated by both Germany and China at the highest political levels. The signing ceremony took place in Berlin, and was attended by Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel, and China’s Premier Li Keqiang.

The size of the investment in the new JV is substantial, as reported in an AP article here,

-

Great Wall put total investment in the venture at 5.1 billion yuan ($770 million) and said it is aiming for annual production of 160,000 vehicles.

The same source noted that:

-

China was MINI’s fourth-largest market in 2017, with 35,000 vehicles delivered, … .

-

Spotlight Automotive Ltd., also will make electrics for the Chinese partner’s brand.

-

The electrics venture with BMW is an important boost for Great Wall, which industry analysts warned would struggle to satisfy Beijing’s sales quotas due to its fuel-guzzling vehicle lineup.

The first Mini EVs produced by the joint venture are expected sometime in 2021.

Great Wall’s New Factories in China, and the Shift towards NEVs

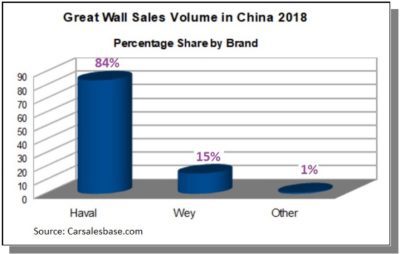

Before delving into the topic of new factories, its useful to briefly revisit where Great Wall as a company currently stands, in terms of its brands, and their associated sales volumes. Exports are fairly negligible, and therefore the focus here is on domestic sales.

Great Wall’s most important brands are Haval and Wey. Together, they represent almost all of the company’s sales.

Haval is by far the dominant brand. Eighty-four percent of the cars that Great Wall sold last year were Haval vehicles.

Haval is by far the dominant brand. Eighty-four percent of the cars that Great Wall sold last year were Haval vehicles.

So it seems pretty clear, that if Great Wall is going to adjust to the new policy realities described above (i.e. the policies that address CAFC and NEV promotion), much of the adjustment will have to be accomplished through the Haval brand. We’ll return to this subject later in the blog, but first lets take a closer look at Great Wall’s new factories, and the types of cars that will be produced at these facilities.

Great Wall’s New Factories in China

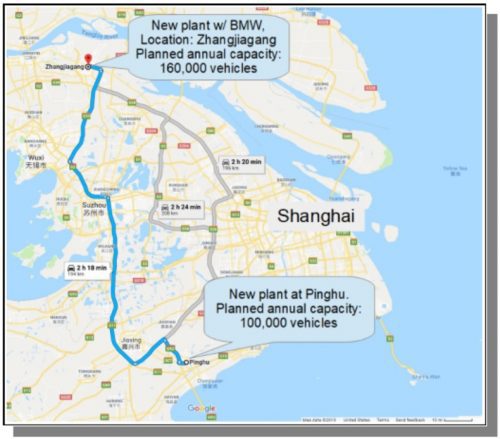

Great Wall’s investments in new factories in China indicate that the company is giving much more strategic importance to the NEV market. The JV plant with BMW, which will be outputting electric Minis and other EVs for Great Wall; has a planned total annual capacity of 160,000 vehicles, and is being funded by a USD 770 million investment. The facility is being built just to the Northwest of Shanghai, in the city of Zhangjiagang, in Jiangsu province.

Approximately two hours south of Zhangjiagang, in the city of Pinghu, another new plant is planned.

Approximately two hours south of Zhangjiagang, in the city of Pinghu, another new plant is planned.

Great Wall’s new plant in Pinghu, will produce a combination of Ora EVs as well as Haval F Series SUVs, according to an article here. The same source, highlights the size of the Pinghu investment at RMB 2 Billion (USD 298 million).

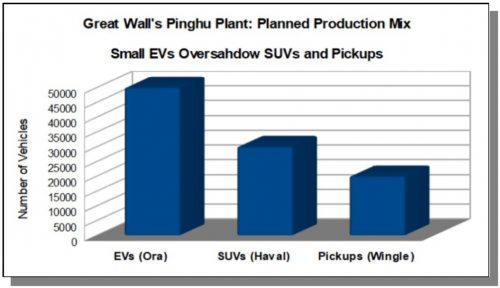

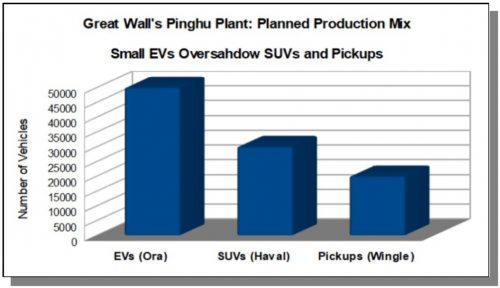

A second source here, includes some details regarding the types of vehicles to be produced at Pinghu. The mix includes both EVs and conventional vehicles (i.e. ICEs). It is interesting to note that Ora EVs will constitute the bulk (50%) of planned production, while SUVs and Pickups together, will account for the other 50%. The graph below highlights planned production at Pinghu, both by vehicle type, and brand:

More recently, last month, Great Wall announced its plans to open up yet another plant on the eastern seaboard, in the province of Zhejiang, in Taizhou city. The reported size of the initial investment is RMB 8 billion (USD 1.18 billion).

More recently, last month, Great Wall announced its plans to open up yet another plant on the eastern seaboard, in the province of Zhejiang, in Taizhou city. The reported size of the initial investment is RMB 8 billion (USD 1.18 billion).

Fewer details are available about the planned production at Taizhou, however, at least one source here, highlights that the facility will produce mostly SUVs. Although Crossovers were not mentioned, given their popularity with consumers, it seems highly likely that Taizhou will be producing Crossovers as well. Parts and components for interiors and chassis will also be produced.

As 2019 progresses, it seems likely to me that we’ll learn more about the types of vehicles that will be produced at Taizhou. As a blogger that focuses mostly on China’s NEV market, I’ll be looking for signs that some of Taizhou’s production capacity will be dedicated to producing at least some SUVs and Crossovers – – that are PHEVs, or possibly even pure EVs.

Three factors almost ensure that China will be seeing more SUV NEVs on the roads in the coming years: a) SUVs and Crossovers remain a growth market, b) the government strongly supports NEVs, and c) concerns about the environment, at least for a segment of car buyers, are influencing purchasing decisions. In an insightful article here, Yang Jian, the Managing Editor of China Automotive News, touched on a) and b) above.

Great Wall’s recently announced 5-2-1 strategy, under the Haval brand, is important in this context. As highlighted here, by INSIDEEVs, the new strategy lays out both an aggressive and ambitious plan for 20 new Haval models by 2023, of which, 60 percent will be electric. The “5” in the strategy refers to a five year plan (2019-2023), the “2” stands for a global target sales volume of two million vehicles by 2023, and the “1” refers to Haval’s ambition to be number one, in the global SUV market.

Given the fierce competition that Great Wall faces, making the above plan a reality will undoubtedly be challenging. But even just achieving moderate to significant success with the 5-2-1 strategy, would yield two major and related benefits for Great Wall. First, the company would be much better positioned to compete in China’s growing NEV market, and secondly, it would address the company’s CAFC challenges and its associated high negative fuel consumption credit score.

In the mean time, as evident with the launching of its Ora brand, and as also evident by its strategic JV with BMW to produce Mini EVs, Great Wall is not standing still to meet these challenges.

If you don’t have enough credits, buy a company that does. Great Wall & Yogomo Motors.

As noted earlier, a manufacturer can remedy a negative fuel consumption credit score with MIIT by transferring CAFC credits from an affiliated company. Motivated by this approach, in September of 2017, Great Wall made a new investment by taking a 25% stake in a smaller EV producing company called Hebei Yogomo Motors. The terms of the deal include an option for Great Wall to increase its stake to 49%.

Great Wall’s 2017 Annual Report here, makes reference to the Yogomo investment. The excerpt below shows the key text, which I’ve bolded, due to its relevance to NEV credits:

The Group obtained 25% of the equity interests in Hebei Yogomo Motors Co., Ltd. (“Hebei Yogomo”) by way of capital increase in September 2017. The Group and Hebei Yogomo will recognize their respective advantages in respect of new energy vehicle and would conduct joint research and cooperate in various aspects, including but not limited to research and development of new energy technology, manufacturing and production techniques, supply of parts and components, establishment of channels and promotion of brand to achieve more economic and social benefits. The transaction will allow the Group to better satisfy the requirements of the PRC government on the new energy vehicle credits.

Similarly, in a China Automotive News Gasgoo article here, key text from the article notes:

Yogomo signed a JV framework agreement with Great Wall Motor (GWM), under which, it made a promise to sell NEV credits to GWM, … and transfer all of its positive corporate average fuel consumption (CAFC) credits to GWM.

Yogomo, as a company, has a history of making small Low Speed Electric Vehicles/LSEVs. LSEVs are often tiny in size, light, and have very limited power. However these bare bones no frills vehicles, have been very popular in China’s rural areas and smaller towns and cities, largely because of their low price. For less affluent Chinese consumers, LSEVs are valued and have great utility. They’re seen as a “step up” and an affordable alternative, to riding a bike or a crowded bus.

For a quick understanding of China’s LSEV market, I highly recommend that readers check out this fun Wall Street Journal video here. It highlights the very substantial size of this market, its appeal to consumers, and some of the challenges for regulators, who are trying to limit, or perhaps even ban, the production of LSEVs. As noted in the video, approximately 1.75 million LSEVs were sold in China in 2017, and so given the size of this market, and the popularity of LSEVs, regulators are going to have their work cut out for them.

In more recent years Yogomo (which now goes under the company and brand name “Link Tour”) has begun manufacturing regular, higher capacity EVs, such as its K-One model pictured here:

Yogomo appears to be a small, but fast moving company with big ambitions. I use the description small because in a July 2017 document here, (filed by Great Wall with the Hong Kong Stock Exchange), Yogomo’s total registered capital at the time of its 2009 founding was reported as a relatively modest RMB 100,000,000 (USD 14.771 million). Between 2009 and 2017, Yogomo, and its business, evidently grew at a rapid pace.

Yogomo appears to be a small, but fast moving company with big ambitions. I use the description small because in a July 2017 document here, (filed by Great Wall with the Hong Kong Stock Exchange), Yogomo’s total registered capital at the time of its 2009 founding was reported as a relatively modest RMB 100,000,000 (USD 14.771 million). Between 2009 and 2017, Yogomo, and its business, evidently grew at a rapid pace.

In a September 2017 article here, Yogomo announced its efforts to upgrade its existing facility in its home province of Hebei, with an investment of RMB 1.8 billion (USD 274.85 million). That seems like a big investment for a company that, less than a decade earlier, had registered capital of less than USD 15 million, i.e. only about 5% of the above mentioned nearly USD 275 million.

As highlighted here, in a China Automotive News Gasgoo article, Yogomo’s investment in its Hebei facility, represents a substantial upgrade. The industrial output value of the investment was estimated at RMB 5 billion (USD 738 million), annual profit and taxes were estimated at RMB 400 million (USD 61 million), while the size of the upgraded project area is 550,000 sq. meters.

Yogomo’s big ambitions, as described in an article here, include a long term target to “… become a world-leading mobility service provider and a NEV maker with market value of RMB 100 billion in 2027.” Although I think its healthy to adopt a humble attitude of – “who am I to question the ambition of others…” – – I’ve also been following China’s NEV sector long enough to know that ambition can often overshadow reality. I’m not going to make any predictions, but still, it might just be kind of fun to check back on this blog, eight years from now, to see where Yogomo stands with its 2027 market valuation ;-).

What is clearer for now is that Great Wall saw some value when purchasing 25% of Yogomo, and also thought it wise to include an option to acquire up to 49% of the company at a later date if it so desires. As noted above, in the reference to Great Wall’s 2017 annual report, a major motivating factor for Great Wall was that “the transaction will allow the Group to better satisfy the requirements of the PRC government on the new energy vehicle credits.” So given this context I thought it might be interesting to look at Yogomo’s Link Tour branded model, the K-One 400 EV SUV , and to estimate the per unit NEV credits that Yogomo generates with each K-One. Remember, with a 25% stake in the company, presumably one quarter of the generated credits go to Great Wall. It’s also important to note that Yogomo is planning five models in total, by 2019, according to an article here.

The specs of Yogomo’s K-One SUV are similar to the Ora iQ compact Crossover. The table below shows both models, and the specs. that determine their respective NEV Credit scores:

Great Wall’s R&D Center in Austria

As noted in an article here, in January of last year, Great Wall announced that it would be creating an R&D Center in Austria, to speed the development of key components for EVs. When explaining their decision to establish the new R&D tech. center, Great Wall highlighted the automotive engineering expertise in Austria, and particularly the expertise related to light weight new materials.

The planned investment in the center is estimated at RMB 157 million (20 million Euro), over a three year period (2018-2020).

The initial focus of the center will be on developing electric motors and related control systems.

Beyond batteries, Great Wall is Keen on Hydrogen and Fuel Cells

Much of the above supports the view that Great Wall is giving greater strategic importance to EVs and hybrids. Taking a longer term perspective, the company is also a proponent of hydrogen powered fuel-cell vehicles.

Much of the above supports the view that Great Wall is giving greater strategic importance to EVs and hybrids. Taking a longer term perspective, the company is also a proponent of hydrogen powered fuel-cell vehicles.

China’s New Energy Vehicle/NEV category (and its related policies and regulations), includes hydrogen powered fuel-cell vehicles (FCVs). These vehicles currently represent a near-zero or negligible part of the market. In comparison to electric vehicles, the technology and the infrastructure that is needed to support FCVs, receives relatively much less attention and support from the government.

Great Wall is making significant efforts to change this. The company would clearly like to see an NEV future market in China, that includes a commercially viable segment for FCVs. This is understandable, because as noted earlier, Great Wall’s CAFC and government policy compliance challenges, are not going to be easily addressed with battery powered vehicles alone. Even though batteries are getting dramatically better, range is still the issue. That would be a non-issue in an alternative future, where fuel-cell vehicles were commercially viable.

That’s a future that Great Wall is advocating for. As described here, on the company’s website, Great Wall’s Vice Chairman and President of the company, Wang Fenying, recently participated in the high level Chinese government’s National People’s Congress, where she put forth “five proposals for the future development of China’s automobile industry and the development of Chinese enterprises.” First among those five proposals was a “Proposal on Accelerating China’s Hydrogen Energy Infrastructure Construction to Promote the Comprehensive and Balanced Development of Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles.”

Great Wall is doing more than just lobbying the government to promote a fuel cell vehicle future. An Automotive News China article here, from last October, provides a useful overview of many of Great Wall’s efforts. These include:

-

An investment in a German company, H2 mobility Deutchland, a German operator of hydrogen fueling stations.

-

Great Wall’s decision to take a 77 percent stake in Shanghai Fuel Cell Powertrain Co., a Shanghai-based fuel cell battery maker.

-

The opening of a fuel cell vehicle tech center at its headquarters in Baoding.

-

The company’s plans to complete the development of a fuel cell vehicle prototype in 2020, and to demonstrate a small fleet of fuel cell vehicles at the Winter Olympics in the north China city of Zhangjiakou in February 2022.

Hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles in the mainstream market, with any significant presence, are more than a few years out. Despite this challenge, Great Wall appears to be committed to doing its part to accelerate the conditions needed for broader commercial viability.

Great Wall is not alone in the Small EV market in China

Many of Great Wall’s competitors, including domestic and international manufacturers, are beginning to compete more visibly within China’s substantial market for small EVs. Often this happens indirectly, through a joint-venture (JV) arrangement, or when a larger company takes a minority share ownership stake, within a smaller company. Great Wall itself is a JV partner with a much bigger partner (BMW) – – as well as a minority share holder and partner of a much smaller company (Yogomo).

Examples of other companies, and their presence (direct or indirect) in China’s market for small EVs, are briefly described below:

- General Motors has a joint venture with SAIC and Wuling, which is known as the SAIC-GM-Wuling JV. The joint venture’s brand Baojun is successfully selling a micro two-seater model known as the Baojun E-100, (a look alike of Daimler’s Smart car).

Over 8,300 Baojun E-100’s were sold in China in January. I’ve written about the Baojun E-100 in detail, in a recent blog here. During January, the most recent month for which data is available, the E-100 finished second on a list, ranking China’s best selling EVs.

Over 8,300 Baojun E-100’s were sold in China in January. I’ve written about the Baojun E-100 in detail, in a recent blog here. During January, the most recent month for which data is available, the E-100 finished second on a list, ranking China’s best selling EVs.

-

In 2017 Volkswagen (VW) created a JV with JAC (Jianghuai Auto), with a focus on the NEV market. The planned investment of the 50-50 JV is six billion RMB (USD 882 million), as noted here. JAC currently offers five models under its iEV line. The smallest is the iEV6E, a small four-door hatchback, in the A00 class.

In 2017 Volkswagen (VW) created a JV with JAC (Jianghuai Auto), with a focus on the NEV market. The planned investment of the 50-50 JV is six billion RMB (USD 882 million), as noted here. JAC currently offers five models under its iEV line. The smallest is the iEV6E, a small four-door hatchback, in the A00 class.

-

Ford has created a JV with Zotye, a small-medium size manufacturer. Last year, Zotye sold just over 232,400 vehicles in China. Within the EV market, Zotye’s best seller was a small two-seater micro, the E200.

The JV between Ford and Zotye, is described in detail in an Automotive News China article here. A brief summary of the partnership, from the same source, appears below:

-

-

Ford Motor Co. is going all-in on electric vehicles in China, the world’s largest market for battery-powered vehicles, … The automaker said Wednesday that it finalized an alliance with China’s Anhui Zotye Automobile Co. to manufacture and sell a full line of EVs. The companies will invest 5 billion yuan ($756 million) to develop the cars they’ll sell under a new brand unique to the Chinese market.

-

-

-

Daimler’s Mercedes-Benz, and its electric brand, “EQ”, will be launched in China later this year.

As noted here, the first EQ launched in China will be an SUV.

Daimler’s has a long established partnership with Beijing Auto (BAIC). BBAC (Beijing Benz Automotive Co.) is a joint venture company between Daimler and BAIC.

In 2017, Daimler and BAIC announced a joint total investment of RMB five billion, (approximately 655 million euro), “for Battery Electric Vehicles and battery localization at BBAC… .”

In 2017, Daimler and BAIC announced a joint total investment of RMB five billion, (approximately 655 million euro), “for Battery Electric Vehicles and battery localization at BBAC… .”Although we don’t know whether the EQ brand will be including small EV’s as part of its product line in China, given the success that Daimler has had with its Smart brand, a similar offering seems at least possible. An EQ concept car, two-seater micro, is shown here.

-

BAIC recently created a spin-off subsidiary called BJEV (Beijing Electric Vehicle).

BAIC recently created a spin-off subsidiary called BJEV (Beijing Electric Vehicle).BAIC, the parent company, owns eight percent of the subsidiary. Daimler has established a 3.93% stake in BJEV, as reported here.

BJEV has a brand called Arcfox, which produces a Mini look-a-like, the Arcfox Lite.

As reported here, both BAIC and Daimler were the two main investing institutions supporting the development of the model.

-

Honda is planning a small EV for China, with a battery supplied by China’s mega battery powerhouse Contemporary Amperex Technology Limited (CATL).

The two partners are reportedly working together to create a small and affordable EV based on Honda’s Fit model.

The two partners are reportedly working together to create a small and affordable EV based on Honda’s Fit model.

The vehicle is expected to cost slightly more than USD 18,000 and have a driving range of about 300 km.

-

The domestic manufacturer Kandi, is producing a small four-door hatchback under the

Global Eagle brand, a brand which is associated with Geely.

Global Eagle brand, a brand which is associated with Geely.

Kandi has a joint venture (JV) with the Geely Holding Group, which is the parent company of Geely Auto.

Although the K23 is being produced by Kandi, at its factory in Hainan, the expectation is that both the factory and the production of the model will be handled by the JV in the future.

For readers that might not be very familiar with China’s geography, Hainan is an island in the South of the country not far from Hong Kong and Macau. Hainan has promoted itself as an eco-friendly tourist destination, and Hainan’s provincial government has plans to eventually ban conventional cars (i.e. Internal Combustion Engines/ICEs) from the island at some point in the future. In the nearer term, the local government is cracking down on LSEVs as highlighted in a Chinese news media article here (tip: Google’s Chrome browser successfully translates this article but the page takes time to load and the translation from Chinese to English is slow; patience required). Considering that Hainan’s provincial government has been supportive of Kandi, and the development of its factory and vehicles, my expectation is that the K23 should sell well, at least in Hainan.

Closing Thoughts

Great Wall’s launching of the Ora brand, represents the company’s first substantial effort to sell into China’s NEV market. Ora’s emphasis on smaller models is probably not a coincidence, because from a cost of production perspective, smaller models are most effective at earning NEV credits. These credits can be used to offset CAFC deficits. For a company like Great Wall, which is reported to have high negative fuel consumption credits, positive NEV credits are particularly valuable.

Likewise, it seems reasonable to infer, that the BMW-Great Wall joint venture to produce Mini EVs, was at least partially motivated by some of these same policy and cost-effectiveness related considerations.

Given that Great Wall’s initial 25% stake in Yogomo Motors was motivated by an interest to acquire NEV credits, it seems likely that if Yogomo begins to establish success in the marketplace with its Link Tour brand vehicles, Great Wall might easily be motivated to take a larger stake in Yogomo.

As noted earlier, Yogomo as a company has roots in the LSEV/Low-Speed-EV sector. LSEVs are particularly popular outside of China’s largest cities, in smaller cities, towns, and rural areas.

It is exactly these same areas, where China’s slowing automobile market, is hoping to find growth. Two ongoing and future developments are going to be worth watching closely. First, there is an initiative to boost consumers demand for cars outside of China’s largest cities. However, as noted in an article here, there is concern that these efforts place too much burden on local governments, with insufficient support from the central government.

Parallel to this, the central government is cracking down on LSEVs, as explained in an Automotive News China article here. Concerns about LSEV related traffic accidents and fatalities, are said to be some of the chief reasons underlying the crack down. China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology estimated that over a five year period, LSEVs were involved in 830,000 accidents and 18,000 deaths. The longer term goal of the crack down seems to be to stop the production and the selling of the LSEVs.

Months and probably years will be needed, before clarity emerges about the fate of LSEVs. What does seem clear though, is that the efforts to crack down on LSEVs, are certain to have an impact on the EV market in China, and particularly that segment of the market that involves small, and very small EVs. In other words, I’m referring to EVs that fall into China’s “A0” and “A00” vehicle classes. Hey wait a minute – – those are the same classes that are most cost-effective to produce – – from an NEV credit perspective. Hmmmm, interesting overlap. 😉

For a full list of references used when writing this blog; click here.

Full disclosure: I own shares in Kandi (Nasdaq symbol kndi) a company that I’m “long” on. I do not own shares in any of the other companies mentioned in this blog.